nLab principal ideal domain

Context

Algebra

Algebraic theories

Algebras and modules

Higher algebras

-

symmetric monoidal (∞,1)-category of spectra

Model category presentations

Geometry on formal duals of algebras

Theorems

Contents

Definition

An integral domain is a principal ideal domain if it satisfies any of these equivalent conditions:

-

Every ideal in is a principal ideal.

-

is a Noetherian Bézout domain

-

is a Bézout domain which satisfies the ascending chain condition on principal ideals

-

is a Bézout atomic domain

-

has a Dedekind-Hasse norm

Often pid is used as an abbreviation of “principal ideal domain”.

To show that definitions (2-4) are equivalent, consider that unique factorization domains and Noetherian domains both satisfy the ascending chain condition on principal ideals. In addition, every GCD domain which satisfies the ascending chain condition on principal ideals is a unique factorization domain. Since Bézout domains are GCD domains, definitions (2-4) are equivalent to each other.

Now to show that definitions 1 is equivalent to (2-4). Every integral domain whose ideals are principal is a Bézout domain by considering the ideals which are finitely generated. To show that these are Noetherian domains and unique factorization domains, we have the following:

Lemma

In a integral domain whose ideals are principal, an element is irreducible iff is a maximal ideal.

Proof

Suppose is irreducible and . Then the ideal generated by is principal, say . Then and since is irreducible, one of is a unit; if is a unit then and thus , contradiction. So then must be a unit, i.e., is the improper ideal. Thus has no proper extension: is maximal.

For any ring , if is maximal and for a non-unit , then the inclusion is an equality by maximality, so for some . Then . In an integral domain we conclude ; thus is a unit.

Theorem

An integral domain whose ideals are principal is Noetherian.

Proof

The union of an ascending chain of ideals is an ideal ; if , then belongs to one of the , whereupon .

Thus, an integral domain whose ideals are principal is a Noetherian Bézout domain.

Similarly,

Theorem

An integral domain whose ideals are principal is a unique factorization domain.

Proof

Working in classical logic, Proposition says that the reverse inclusion relation on the set of nonzero ideals is well-founded. Let be the subset of ideals that are products of finitely many (maybe zero!) maximal principal ideals. For any proper ideal , if every properly containing can be factored into maximals, then so can . (Spelling this out: either is maximal/irreducible, or factors as where both and are non-units; and factor into maximals by hypothesis, and therefore so does .) Thus is an inductive set, so by well-foundedness it contains every ideal , i.e., can be factored into irreducibles.

For uniqueness of the factorization, we first remark that if is irreducible and , then or . (For is a field and thus a fortiori an integral domain, so that if , then or .) Thus if are two factorizations into irreducibles of the same element, then divides one of the irreducibles , in which case and each is a unit times the other, meaning we can cancel on both sides and argue by induction.

Thus, an integral domain whose ideals are principal is a Bézout unique factorization domain.

It remains to show using classical logic that every ideal of a Noetherian Bézout domain or a Bézout UFD is a principal ideal… (to be done)

Examples

-

any field

-

the ring of integers

-

a polynomial ring with coefficients in a field (in fact, for any commutative ring , the ring is a pid if and only if is a field)

-

a discrete valuation ring (for example, a ring of formal power series over a field)

-

any Euclidean domain

-

in the ring of entire holomorphic functions on every finitely generated ideal is principal (Helmer 40), but the ring is only a Bézout domain.

That both the integers and the polynomial rings over finite fields are principal integral domains with finite group of units is one aspect of the close similarity between the two that is the topic of the function field analogy. That also the holomorphic functions on the complex plane form a Bézout domain may then be viewed as part of the further similarity that relates the previous two to topics such as geometric Langlands duality. See at function field analogy – table for more on this.

Structure theory of modules

Free and projective modules

Theorem

If is a pid, then any submodule of a free module over is also free. (For the converse statement, see here.)

Proof

By freeness of , there exists an isomorphism , a coproduct of copies of (as a module over the ring ) indexed over a set , which we assume well-ordered using the axiom of choice. Define submodules of :

Any element of can be written uniquely as where and . Define a homomorphism

by . The kernel of is , and we have an exact sequence

where is a submodule (i.e., an ideal) of , hence generated by a single element . Let consist of those such that , and for , choose such that . We claim that forms a basis for .

First we prove linear independence of . Suppose , with . Applying , we get . Since , we have (since we are working over a domain). The assertion now follows by induction.

Now we prove that the generate . Assume otherwise, and let be the least such that some cannot be written as a linear combination of the , for . If , then , so that for some , but this contradicts minimality of . Therefore . Now, we have for some ; put . Clearly

and so . Thus for some . At the same time, cannot be written as a linear combination of the ; again, this contradicts minimality of . Thus the generate , as claimed.

Since the integers form a pid, and abelian groups are the same as -modules, we have

Corollary

(Dedekind) A subgroup of a free abelian group is also free abelian.

Remark

The analog of this statement for possibly non-abelian groups is the Nielsen-Schreier theorem.

Also, since projective modules are retracts of free modules, we have

Corollary

Projective modules over a pid are free. In particular, submodules of projective modules are projective.

Normal forms

Proposition

(matrices over principal ideal domains equivalent to Smith normal form)

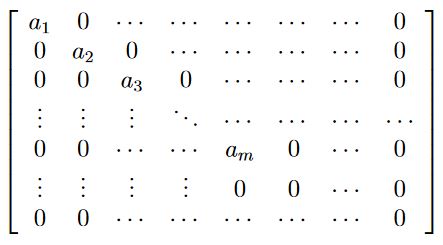

For a commutative ring which is a principal ideal domain, every matrix with entries in is matrix equivalent to a diagonal matrix filled up with zeros:

There exist invertible matrices and such that the product matrix is a diagonal matrix filled up with zeros:

such that, moreover, each divides .

For matrices with coefficients in the pid of integers see also

Torsion-free modules

Proposition

A finitely generated torsionfree module over a pid is free.

Proof

Let be a finite set of generators of , and let be a maximal subset of linearly independent elements. (Unless , then has at least one element, because is torsionfree.) We claim that can be embedded as a submodule of the free module generated by (which in turn is the span of as a submodule ). By Theorem , it follows that is free.

Let be the elements of . It follows from maximality of that for any , there is a linear relation

with . For each in the complement , pick such an , and form . Then the image of the scalar multiplication factors through , and is monic because is torsionfree. This completes the proof.

Proposition

Let be a pid. Then an -module is torsionfree if and only if it is flat.

Proof

Suppose is flat. Let be the field of fractions of ; since is a domain, we have a monic -module map . By flatness, we have an induced monomorphism . For any nonzero , the naturality square

commutes, and since the map is multiplication by a non-zero scalar on a vector space, it follows that this map and therefore also is monic, i.e., is torsionfree.

In the other direction, suppose is torsionfree. Any module is the filtered colimit over the system of finitely generated submodules and inclusions between them; in this case all the finitely generated submodules of are torsion-free and hence free, by Proposition . Thus is a filtered colimit of free modules; it is therefore flat by a standard result proved here.

Structure theory of finitely generated modules

structure theorem for finitely generated modules over a principal ideal domain

In constructive mathematics

First of all, in constructive mathematics, there are various notions of integral domains, such as Heyting integral domains and discrete integral domains. These already result in multiple notions of principal ideal domains, such as Heyting principal ideal domains and discrete principal ideal domains.

In addition, the various definitions of principal ideal domains do not coincide with each other in constructive mathematics. For example, consider the classically true equivalence of discrete Bézout unique factorization domains and discrete integral domains where every ideal is principal:

Theorem

Given a discrete Bézout unique factorization domain , every ideal of is a principal ideal if and only if the law of excluded middle holds.

Proof

In one direction, the usual proofs rely on being able to decide whether any particular element of belongs to the ideal or not. For the converse, let be an arbitrary proposition. Consider the ideal . By assumption, it is generated by the elements of . Since is a discrete integral domain, it holds that or . In the first case holds, in the second .

It is unknown whether in the absence of excluded middle, there are Heyting integral domains where every ideal is a principal ideal. But with Heyting integral domains, maybe we should be talking about principal anti-ideal domains instead of principal ideal domains.

See also

References

-

O. Helmer, Divisibility properties of integral functions, Duke Math. J. 6 (1940), 345-356.

-

Wikipedia, Principal ideal domain

-

Eric Wofsey, Principal Ideal Domains, (written for Mathcamp 2009) pdf

-

Henri Lombardi, Claude Quitté (2010): Commutative algebra: Constructive methods (Finite projective modules) Translated by Tania K. Roblo, Springer (2015) (doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9944-7, pdf)

Last revised on January 11, 2025 at 20:27:26. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.